It is not only the children, but also the parents, that must be taken care of during the Corona crisis.

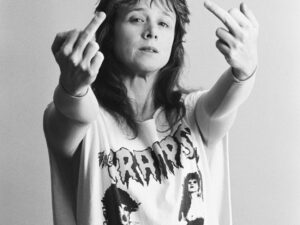

In the future, will caring for our next of kin cost us individual freedoms? Will it be worth it? A self-questioning by the writer Caroline Rosales

“They only show Turks and Blacks on TV, on every channel.”

My grandma zaps through the channels with the remote control.

“Okay, then change the channel,” I say, annoyed.

“Oh, it’s the same on every channel.”

When I was twelve and my grandmother was very old, almost eighty, I did my best to visit her as often as possible. I took the regional express to Bad Neuenahr, bought flowers at the station. She presumably died of lung cancer. She had always been a heavy smoker, my parents told me. During the war, she rolled her cigarettes from tobacco crumbs and cherry tree leaves. She did this until the 1950s; by that time, filter cigarettes were available at every kiosk.

My parents always had heated discussions when it came to my grandmother. The worry that they would have to finance a nursing home kept them awake at night. But it never came to that. My grandma died in a hospital in the mid-1990s. My father was 50 years old at the time. My mother was 65 years old when her mother died. And my friend’s mother cared for her mother at home until she was 75 years old. When her mother passed away at the age of 95, it was like the beginning of a new life for her, too.

Nowadays, our parents often accompany us until we have reached retirement age. Whereas the average life expectancy in 1871, the year the German Reich was founded, was 35.6 years for men and 38.4 years for women, today, the average life expectancy in Germany is 78.5 years and 83.3 years, respectively, according to the Federal Agency for Civic Education.

In times of corona, of new lockdowns and possible second and third waves, there is a greater desire for familial togetherness. I am 38 years old, my mother 70, my father 75, and in ten years I will be 48. Of course, neither of my parents likes to hear that they might be dependent on care. And yet, my thoughts are still spiraling. In March 2020, the first lockdown occurred almost overnight. Kindergartens and schools remained closed. It was announced less than 24 hours beforehand. All of a sudden, there was no more state infrastructure. I stayed at home with three small children. During the day, my daughter breathed on the windows and drew flowers with her finger.

I took care of everything and cooked for six people. My mother was there, too. Just as a generational conflict demands. The elderly who are incapable of meeting their own needs are always a burden. But in societies where there is a degree of equality, every mature person knows, even if they don’t want to admit it, that they will be in the same position tomorrow as the elderly are in today. That is the moral of the Grimm brothers’ fairy tale: A farmer makes his elderly father eat out of a wooden bowl, seated away from the family. One day, his son surprises him by carving a wooden bowl. “This is for you when you’re old.” Immediately, the grandfather is restituted to his place at the table again.

Active members of the community must make a compromise between their long-term and immediate interests. I, too, hope to be treated with dignity by my daughter in my old age. If I did not visit my mom and my grandma as I once did, I would have no justification to demand the same later.

My grandma was the only elderly person I accompanied for a longer period. When I visited her as a young girl, I would sit on the stool next to her. Because I couldn’t stand court TV, I always looked around for some spontaneous task, but in reality, I felt resigned.

Order and never throwing things away was in my grandma’s genes. Postwar generation. “We had nothing.” But the Russians, my grandmother always said, did not let her starve. She acted like a lady of the world who read diet and fashion magazines. But when I didn’t eat my macaroni as a child, her eyes would tear up. She passed the trauma of not having possessions on to my mother.

Unlike in my apartment, every scrap that made it to my mom’s house is art. Every paper flower, every picture frame, every empty perfume bottle, the statue of the Virgin Mary with flaked paint, the patchwork blanket on which my cat sat thirty years ago, every object and every bit of garbage is worth keeping to my mom. Old tickets, tourist brochures from city trips, foreign coins, stamps and notepads, pages torn out of fashion magazines and cheap souvenirs are all treasured.