“At the end of the path, complete darkness awaits.”

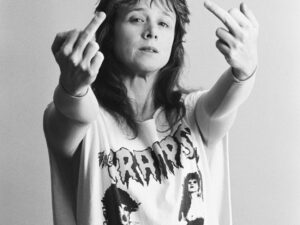

Author Mely Kiyak is one of the most impressive journalistic voices in the country. In her political columns, she analyzes structural right-wing radicalism and racism, criticizes misconduct by the police authorities, and the exploitation of people under capitalism. In return, she has repeatedly been met with hatred and violence. In her new book, womanhood (“Being a Woman”), she turns her gaze to herself. It became a quiet and tender, but also disturbing, text. It repeatedly deals with the barbarism of the West, the lack of culture and substance in our society. What does it mean to be a woman under these conditions, to write from below, to raise your voice?

A conversation about sensuality, freedom, loneliness and shame between Mely Kiyak and Ruben Donsbach

Miss: Mely Kiyak, womanhood begins with the sudden loss of your eyesight. With your final moments of sight, you observe your naked body, breasts, the “triangle between the legs, this enormous nakedness with all its curves and gradations.” Why did you experience a sense of shame at that moment?

Kiyak: Shame is part of cultural etiquette. My parents are Kurds; their religion is Alevism. The bodies are naked at birth, in love and in death; beyond that, there is no practice of self-inspection. I had little interest in an optical evaluation of my body until the day I developed this disorder and the image literally disappeared in front of my eyes. Then a desire to look at myself very closely became almost overpowering. I had to say goodbye to myself with one last look.

You were a spiritual being?

Totally. I was the most incorporeal person in the world. Until I turned twenty, I was a perfectly functioning machine. I was small and delicate, but I felt strong. In my imagination, I was more of an elephant than a mouse.

But at some point, you became aware of your own body and its features?

I avoided my own intimacy. In my early twenties, I confessed to a man that I had never looked at myself. He couldn’t believe it. I discovered my body through desire and found it all scandalous in a positive sense. Outside of love, I was spiritualized, dreamy, and physically absent.

What was this world that you drifted into like?

A misty place from which I began to orientate myself and explore the world.

What did you discover there as a child and teenager?

The most incomprehensibly commonplace things in the world.

Describe some of them.

When my mother soaked chickpeas in water overnight, the next morning they were soft and you could flick off their thin skins. I couldn’t get over that. What was happening? When my girlfriends would take me to a café, I was amazed at the ice piled up in the glasses. It is not an act when I say that I was insanely ignorant and dumb for a long time. Everything was foreign and seemed miraculous.

It sounds as if you had a microscopic view of the world, much like a researcher.

I couldn’t grasp connections at a glance. I could only approach life minimally from a specific perspective. The view of the whole was missing. You know, even then my field of vision was very limited, but that was diagnosed much later.

I imagine that you saw the world with a kind of magical realism.

When I was twelve or thirteen, my cousin once asked me if I had ever noticed that the color of women’s lips was the same color as their nipples. I replied: What is nipple color? The breast has a second color? And a nipple? My cousin really thought I had lost my mind.

There is a wonderful passage in your book. You describe how you accompany a cousin to a meeting with her fiancé in a Kurdish village. The two disappear to make love; the cousin comes back and tells you everything in detail. Among other things, he “kissed her below” and describes it as “sucking the flesh out of an upside-down fig. It was like putting a soup bone in your mouth and sucking out the marrow. “

[ laughs ] This is literature, of course.

But the language is yours. It seems naive and feminist at the same time, because it takes a radically poetic approach to sexuality.

But the question is: How does one write about intimacy? Aesthetically, that’s a big problem. I thought about it for a year, almost went crazy.

What’s the solution?

You have to leave the familiar formulations behind. In the West, we learned to describe oral love practices, to give just one example, something like this: Part the labia, place the lips on it, and the tongue goes in. This language is composed of sex therapy and pornography and strives for total technical accuracy in the description. I didn’t want that. I wanted to find other comparisons. Caressing a woman’s breasts is like soaping the heads of twins at the same time. The tip of the breast is like deciphering Braille. That is more accurate.