Beauty is such a loaded term, especially when applied to humans. The body positivity movement regards all bodies positively, irrespective of size, shape, skin tone, gender, and physical abilities. Because judging others based on their physical appearance is discriminatory. Calling someone ugly is hurtful, considered even more damaging than calling them dumb or mean.

Reclaim Ugliness

What philosophical aesthetics and the body positivity movement have in common, is that they have both failed to come up with a universal definition of what a beautiful person actually looks like. Instead, we dodge it with proverbs such as: Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Or, as actress Emma Watson famously stated: “Feeling beautiful has nothing to do with what you look like.” Well, that’s easy for her to say.

The thing is, though, that when it comes to popular media culture, the images we are fed every day, standards of beauty appear to be obvious. The beautiful woman is, more often than not, young, thin, white, cisgendered and able-bodied – all terms that we have come to loathe as being excluding, dictated by patriarchy and neoliberal self-optimization ideology. This is, of course, not wrong. But does the solution of this dilemma really lie in the expansion of the concept of beauty to include, in theory, every single person that exists?

“If everybody is beautiful, then no one is. The recognition of beauty presupposes the existence of ugliness.”

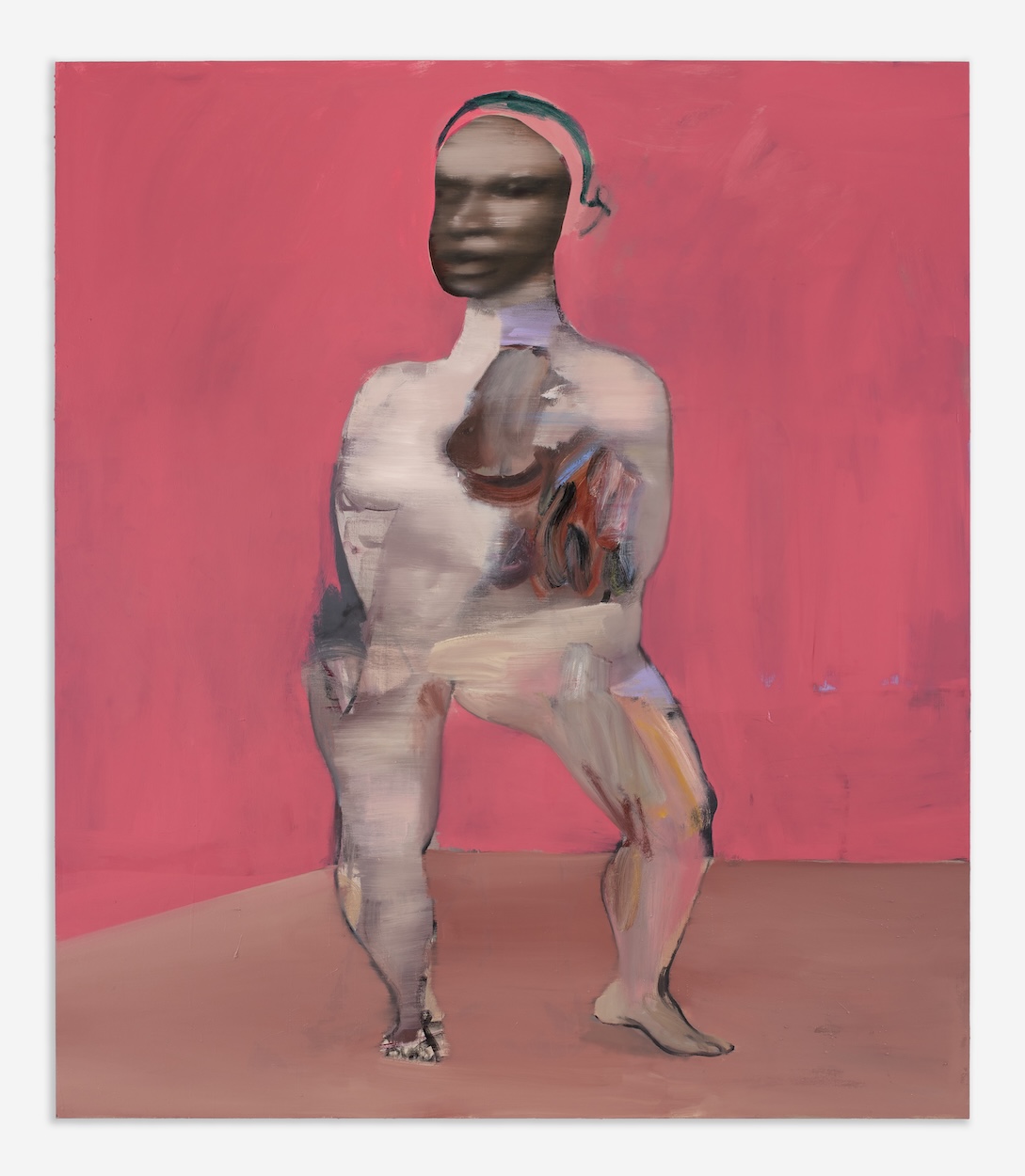

George Rouy, Grounds of a Broken Heart, 2022

We’ve all heard the slogans: ‘There is no wrong way to have a body,’ or simply, ‘Every body is beautiful.’

Hashtags such as #effyourbeautystandards, #celebratemysize and #mermaidthighs promote diverse representations of bodily beauty. The fashion industry has also taken note. In the last few years, casting strategies have started to change. At recent fashion weeks – though the trend has rolled back a bit – runway shows routinely included models of diverse ethical backgrounds, body types and gender identities, as well as older models and models with visible disabilities, rocking wheelchairs and prosthetic limbs.

Sometimes, one can’t help but feel that it seems like a circus of attention, a competition to see who can gather the most spectacular deviations to promote the progressive values of their brand.

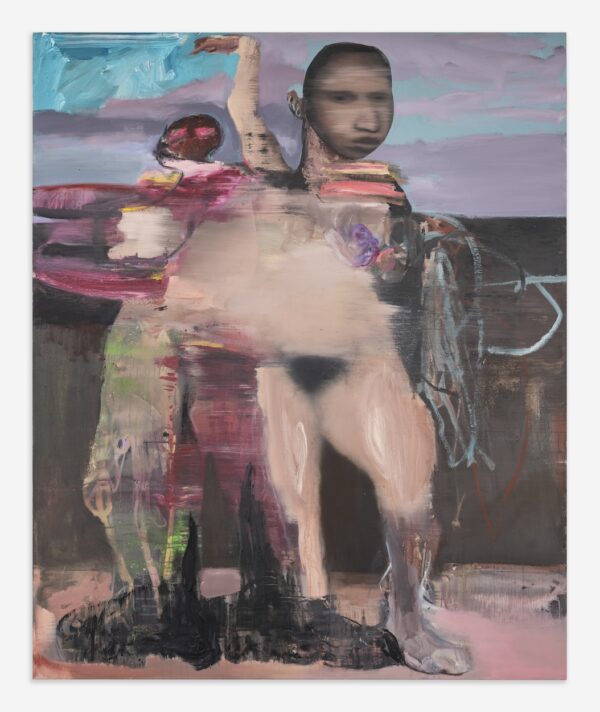

George Rouy, Finishing Pose, 2021

George Rouy, Standing in Half, 2022

While most would agree that this is at core still a positive development, the question remains if beauty is truly the best umbrella term to describe all these different bodies. Because when beauty becomes the only currency for valuing them, we remain stuck in the same harmful paradigms we aim to destroy.

A person’s worth cannot be tied to their beauty (or lack thereof). Beauty is a thing of rarity, an exception, not the norm. If everybody is beautiful, then no one is. The recognition of beauty presupposes the existence of ugliness.

We all know ugliness exists, we see it every day, but admitting to this simple fact seems like a social taboo. Perhaps there is something to be learned from body positivity after all: The fat acceptance movement has worked hard to remove stigma from the word “fat,” claiming it is not an insult, just a descriptor – since fat does not equate with unattractive.

Should the term “ugly” be rehabilitated in the same way?

There are some good arguments in favor of reclaiming ugliness. In his essay “On Ugliness” (2007), philosopher Umberto Eco writes:

“Beauty is, in some way, boring. Even if its concept changes through the ages… a beautiful object must always follow certain rules. A beautiful nose shouldn’t be longer than that or shorter than that, on the contrary, an ugly nose can be as long as the one of Pinocchio, or as big as the trunk of an elephant, or like the beak of an eagle, and so ugliness is unpredictable, and offers an infinite range of possibility. Beauty is finite, ugliness is infinite like God.”

Radical feminist Mary Daly predated Eco by almost three decades. In 1979, she published her classic book Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism, in which she challenged women to embrace the stereotype of the ugly old spinster, the hag, as she called it, as a gesture of rejection of the male gaze. A woman who derives her self-worth from her beauty will always be dependent on others, while an ugly woman can do whatever she pleases.

“Hags live. Women traveling into feminist time/space are creating Hag-ocracy, the place we govern. To govern is to steer, to pilot.”

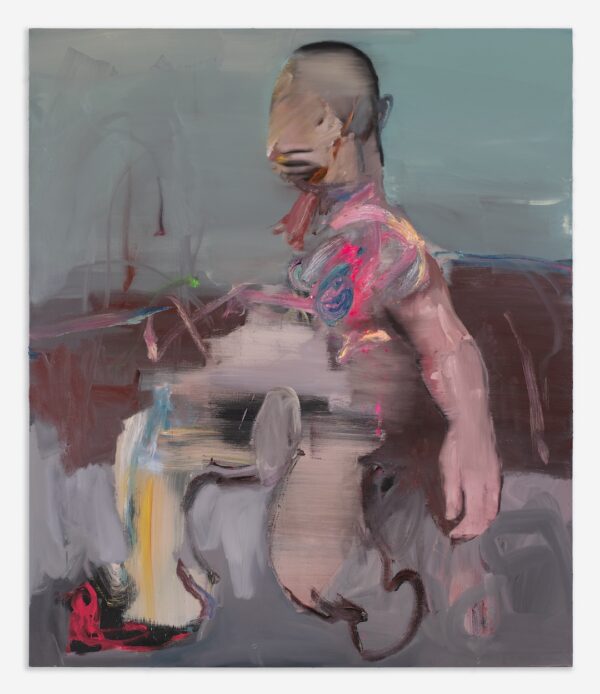

George Rouy, Heavy Feet Walking Away, 2021

Daly finds an unusual ally in Anton La Vey, the notorious founder of the Church of Satan, who famously dated (and possibly hexed) iconic Hollywood bombshell Jane Mansfield in the 1960s. In 1971, he published The Satanic Witch as a guidebook for women, instructing them on using psychological manipulation and glamorization techniques to access money, power and sexual fulfillment. As La Vey puts it, ugliness is a blessing in disguise, an obstacle that can easily be turned into a steppingstone. He writes: “The truly ugly girl has others at a disadvantage, because rather than hurt her feelings, they will do things for her out of guilt.”

La Vey is convinced that all women can use glamor to their advantage, but they should do this according to type. Flaws should not be concealed, but rather emphasized. “If you are really ugly, you must capitalize on your grotesqueness.” He continues: “Do everything else in accord with your type. You will then be perfect, but strange looking, and that will confound others. You will be outrageous, because everything about you will fit, despite your homeliness; and with your hint of secret powers, the small-minded will fear you, and well they should, for should you follow this advice, you will have those powers.”

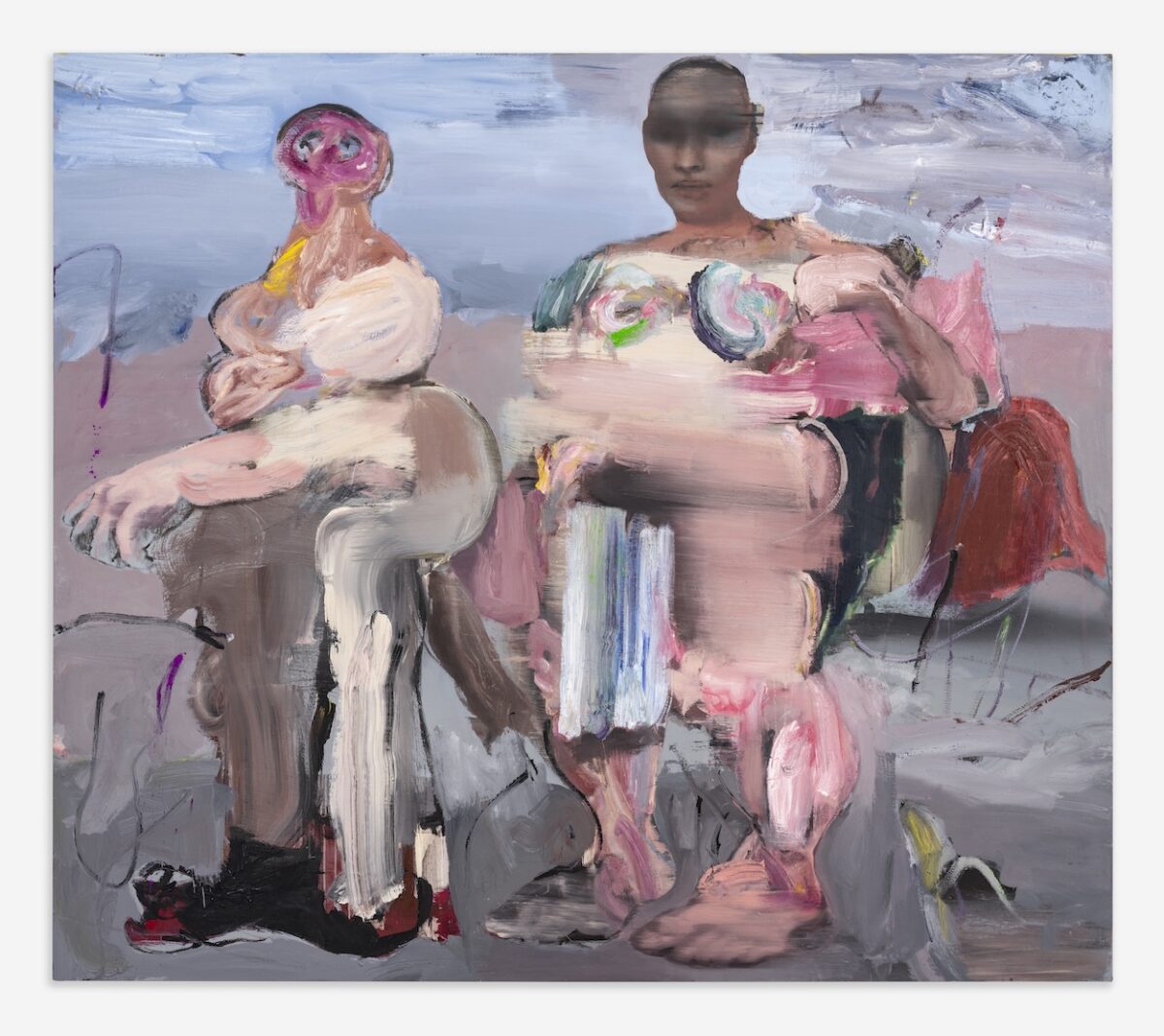

George Rouy, Carry Me, 2021

In recent years, several younger feminists have taken a critical look at the concept of ugliness. In 2018, the researchers and writers Sara Rodrigues and Ela Przybylo published the compilation On the Politics of Ugliness, that explores concepts drawn from art history, critical race theory, psychoanalysis and critical theory to fight against “visual injustice.” Visual artist and curator Moshtari Hilal followed with an intimate and poetic collection of thoughts in 2023, reflections and personal experiences simply called Ugliness. In the same year, writer Lauren Elkin published Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art, exploring the attributed (and self-proclaimed) monstrosity of self-determined women.

“[T]he monster stands for everything a society attempts to cast out. Monsters dwell at borders; you might even say the monster creates the border. Everything that is acceptable over here; everything that is not over there. But these lines have never been fixed.”

Ugliness, like beauty, is an ascribed term.

If everybody can be beautiful, everybody can be ugly.

The positions on the scale are not affixed, either, they might change from day to day, as we enter different rooms, are seen with different eyes. Still – and this is the secret power of ugliness, what makes it so scary – being ugly puts you in the position of the outcast, the rebel. While beauty stands for catering to the hegemony and passive objectivity, ugliness is the province of the unseen and repressed; thus, embracing the concept becomes a form of visual resistance.

Words by Diana Weis