WE NEED MORE FLOWERS

“For contemporary self-images of porous masculinity as well as transcending femininity, these artistic, abstracted silhouettes of flowers are wonderfully suitable as a projection surface for variant sexual self-definitions. They are suitable for verifying a new language of sexual desire in a society that communicates via visual signs. The cycle of blossoming and wilting is one of constantly becoming.”

The transfiguration of the female body in floral metaphors is an evergreen of art and poetry. Young women “blossom” before they finally “wither;” they are fragrant like a bouquet of roses; their sexual organ has been innumerably depicted as the opened calyx of a flower, which is finally “deflowered,” with “deflower” meaning “to have sex with a woman who has never had sex before,” according to the Cambridge Dictionary. The passive female flower is actively deflowered by the male.

This is, of course, extraordinarily old-fashioned and rightly scandalous in the current discursive climate. No woman can seriously identify with the passivity of a narcissus swaying in the summer breeze in a vast meadow. This late-romantic habitus, of masculinity that is at least deeply psychologically aware of its transience, will surely soon be overridden.

But, in art, the delicate silhouette connoted as feminine, deliberately and indistinctly marking the transitional zone between the body and the organic in an arched and light manner, could once again unfold an uncanny emancipatory potential in the emerging – if not classless, then perhaps genderless – society.

The connection of flower and, above all, female body has always experimented with associations of fragility: the soft form bent in the wind, fragile and ornamental, in need of protection and, precisely in this elusive fleetingness, extremely sexualized and fetishized. It is the flower that wants to be plucked, but also protected. The ideal female body not only appeared in the literary projections of the Romantics, but also on the screens of modernist movie theaters as floral became increasingly androgynous.

One finds the connection between female bodies bending almost like butterflies over water lily ponds and blossoming in spring meadows prominently in Claude Monet’s impressionist paintings. For example, in Woman with a Parasol (1875), Camille Monet and a Child in the Artist’s Garden in Argenteuil from the same year, or Young Girls in a Rowboat (1887). In the latter, in particular, it almost seems as if the female bodies merge in color with those of the water lilies on the water. An implied abstraction that Henri Matisse brought to flower in his sea-blue cut-outs as the ultimate heightening of the floral silhouette and metaphor. Matisse’s Nu Bleu completes the marriage of the sexualized body with the organic form of the plant. The limbs on these nudes seemingly caress or entwine with each other. This iconography is a cultural sign that points to the future in which we find ourselves today. For it is precisely in this extremely abstracted floral pose that an inter- or transsexual corporeality manifests itself. For contemporary self-images of porous masculinity as well as transcending femininity, these artistic, abstracted silhouettes of flowers are wonderfully suitable as a projection surface for variant sexual self-definitions. They are suitable for verifying a new language of sexual desire in a society that communicates via visual signs. The body becomes a fluid, ever newly unfolding and withering flower dream.

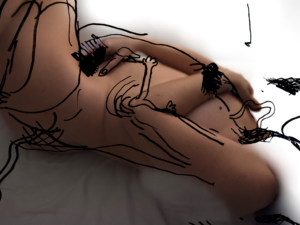

One example: Addie Wagenknecht, who is represented by König Galerie, has intensively studied the works of Yves Klein, especially the Anthropometries performances. Anthropometry means the measurement of the human body. Klein had naked women – bathed in the navy blue of his predecessor Matisse – press shapes onto the canvas. If you look at these forms today, they seem far more organic, floral and lively than Matisse’s model. Wagenknecht abstracts and radicalizes even further, letting software and robotics do the work. These “performances” are not regarded as a process, but only as a result: as negative space. A modern body consciousness takes shape here in a line of artistic tradition which takes its origin in the floral and ultimately vanishes completely in an overgrown reflection.

With a bit of code-switching, the mimosa, a tropical plant species, could become the archetype of our new body type. According to the encyclopedia, the mimosa is “used metaphorically for a very sensitive and oversensitive person; or a person recovering from illness.” It is also known as a “shamefaced sense plant.” This odd pair of terms – sense and shame – suggests that shame is caused by sensitivity and oversensitivity. There is no better way to portray the human condition at the dawn of the twenty-first century.

Yet there is an emancipatory potential in the sexual fluidity of the human being shamefully thrown out of the garden of Eden. The cycle of blossoming and wilting is one of constantly becoming.

Since we have all been left restricted and void of social and physical interaction, we can empathize with the yearning and longing for basic human contact, the new normal. Touch is more important than ever, we all miss the feel of touching one another, a basic desire and source of pleasure for all. We want to be together, the new together, transcending the barriers and finding what brings us closer. Realness is the key in making us all come together, focusing on what really matters and our essential needs. We need more beauty, and that’s why we need more flowers.